CLR James, Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution. Around the kitchen table with graphic novel creators Nic Watts and Sakina Karimjee.

- Adam Reeves

- Dec 23, 2024

- 11 min read

Updated: Jan 6, 2025

The most successful uprising of enslaved people in history is depicted in this stunning graphic history.

Interview and text by Adam Reeves.

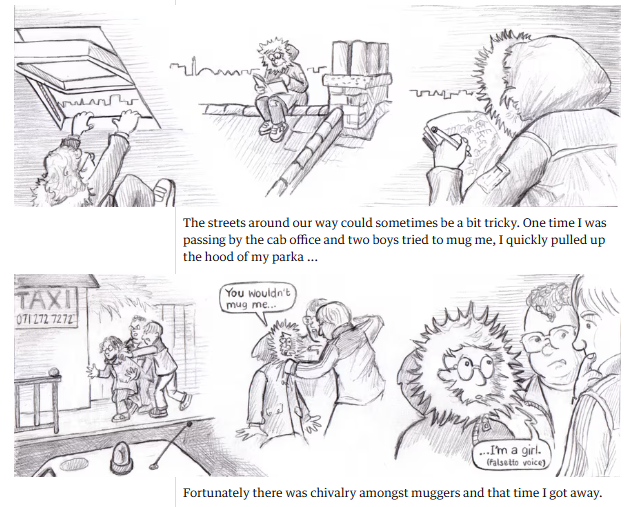

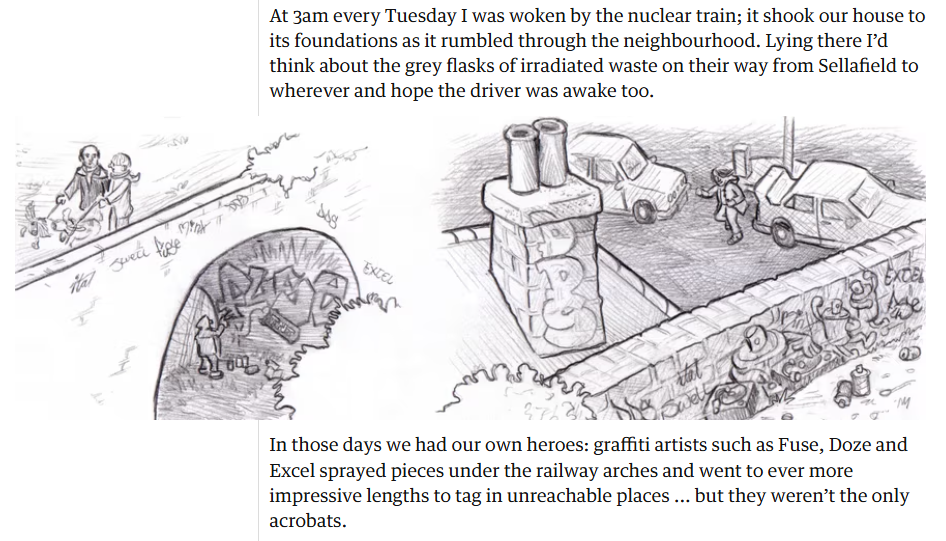

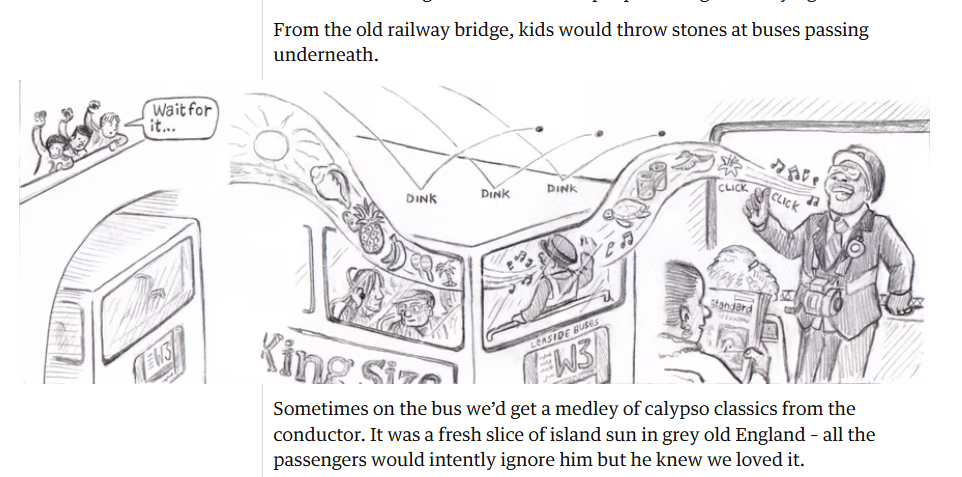

In June 2024, directly after the Guardian ran a feature reflecting upon ska trombonist Don Drummond's 90th birthday, with ample reference to my Trombone Man comic book project, I received a brief message from a UK illustrator called Nic Watts. He too, had coverage by the Guardian some years before, a self-written piece about his teenage sketches of 1990s North London street life viewed from his rooftop perch above his family home. Calypso bus conductors and acrobatic drug dealers: a bird's-eye view of 90s north London, was the caption and showcases a selection of Nic's work from the era, capturing something of the essence of the Stroud Green neighbourhood of Hackney, long before the craft breweries, coffee roasteries and sourdough bakeries moved in.

Scroll through to see the full piece.

The by-line mentioned that he was also working on a graphic novel about the Haitian revolution led by its formerly enslaved people, which piqued my interest. We established that we were based near each other on the South Coast, both London escapees, so decided to meet up to compare notes on being comics creators. After an enjoyable first meeting, I asked if I could interview Nic and his collaborator, Sakina about how their book came into being. Sitting around the kitchen table in their family home, the pair shared with me the story behind their graphic novel, Toussaint Louverture. I must confess I knew very little about Louverture, or the Haitian revolution, or CLR James who's work they have adapted, so the book and our subsequent discussion was a fascinating dive into this hugely significant and often overlooked chapter of black history.

Adam: So, who was Toussaint Louverture and why is he important?

Nic: Toussaint Louverture was a leader during the Haitian Revolution, which started in 1791 and finished in 1804 so it was spread over the course of twelve years. It was an uprising against slavery in the French colonial plantation economy of Saint Domingue, which then became Haiti. At the beginning of the revolution, there were lots of different leaders, but Toussaint Louverture rose to prominence because he was extremely clever. He could also write and was also a physician. He also had to look after animals and stuff like that. And he was just an amazing, natural born leader. Haiti, or San Domingue, as it was then, was the world's most profitable colony at this time. It produced more profit than the whole of the British West Indies put together. It was producing coffee, indigo and most principally sugar. But the reason that Haiti was so profitable wasn't because the people were more motivated there, or anything like that. It was because the slave system was highly industrialized and incredibly brutalized. Saint Domingue had some of the most industrialized spaces on the on the planet at that time, and that enabled these people to be highly exploitive.

As a politically aware teenager, Nic was inspired by the work of Trinidadian writer CLR James. Born in 1901, James left Trinidad for Britain, also living for a time in the US. He was a historian, political activist, novelist, playwright, and journalist, most notably as a cricket correspondent for the Guardian. His novel, Minty Alley, was the first prose book to be published by a black person in Britain. James' wrote an important history book, the Black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution, which details how enslaved peoples of Saint Domingue took on the most powerful colonial army on Earth and created the country of Haiti. Louverture was the cunning military leader who outwitted the French, the Spanish and the English, the most successful uprising of enslaved people in history. The inspirational story had fired Nic's imagination and upon returning to it as an adult, Nic hit upon the idea of turning the Black Jacobins into a graphic novel. It seemed that few people really knew about Louverture. Abolition of slavery had been overshadowed by the more mainstream narratives pushing the idea that it was white liberal reformers like William Wilberforce who liberated enslaved peoples. The truth is far more complex and radical. While James' book served as a resource for the tumultuous history of the period, it didn't exactly lend itself to direct adaptation. With Sakina's many years experience of working in theatre, her instinct told her they would need something more than a history book as their source material. She explains:

Sakina: Well, I just couldn't see how we interpreted all that into a graphic novel. I was like, 'we need dialogue, we need narrative. What we need is a play'. And I said, 'has anyone written a play of the Haitian revolution?' Because that would be a perfect thing to try and adapt.

Nic did some research and discovered that four years before publishing the Black Jacobins, CLR James had, in fact, written a play about the Haitian slave revolt, called Toussaint Louverture, although it was somewhat shrouded in mystery. Being the first play ever performed in England to be written by a black playwright with a cast of black professional actors, James' play was performed just twice, at the Westminster Theatre, starring American black actor and singer, Paul Robeson as Louverture. The original script had been lost for 70 years and there was nobody still alive who remembered seeing it, so the play had slipped into the realms of mythology. In 2005, an historian called Christian Høgsbjerg stumbled across the lost script in a library while doing some research on Louverture.

Nic: It's a really important part of British theatre history. What was crazy was that it was discovered in 2005 but didn't get published till 2013. I must have had the idea in late 2012. Then I contact Christian, the historian, about it in 2013, and he's like, 'Oh, it's coming out in three months time, as a play'.

CLR James' re-discovered script, published 2013.

Høgsbjerg's book told the history of the play, along with essays, photos and other historical documents. The timing was uncanny and seemed to Sakina and Nic that the stars were aligning. Fortunately for them, the play was of a high enough standard for them to adapt.

Nic: It was a relief when it was good. I would have been very disappointed if it was rubbish, but it was brilliant. I read the first two scenes, and I was just, 'wow, this is amazing'. And then I read the third scene, and I was like, 'oh my God, how am I going to do this? This is difficult!' But its so brilliantly written, so concise and so lean. There's not a word in there that doesn't need to be in there. That's one of the reasons that our book is verbatim to the original script, because the play is so concise and well written. And of course, he plays around a bit with history, like any writer of a fictional account of a historical event will be able to do.

Sakina: He (James) was a Marxist, and he developed Marxist theory through his life. He was very involved in anti-colonial struggles in the Caribbean and in Africa and developed Marxist theory around anti-colonialism.

Nic: So he's not just a Marxist as much as, like, an activist. He's actually a Marxist thinker, someone who is changing the political course of the time. The guy is quite an amazing character. Lived an amazing life. He died in 1989, in his late eighties.

Nic: He lived through amazing change and a lot of amazing disappointment. He had great hopes for these new nations in the Caribbean and Africa that were throwing off the yoke of colonialism and then very disappointed by what came out of that, you know, just more sort of oppressive governments, but, you know, an amazing optimist, which all Marxists have to be (cracks up laughing!).

The life of CLR James has been extensively documented in numerous biographies

As someone who is adapting a biographical book into a comics script myself, I can fully appreciate the difficulties that the pair must have been up against. One of the obvious challenges is that the passage of time in a stage play is different to the way time passes through the pages of a comic book. Comics have their own set of rules and constraints as to how time functions, which are quite different to any other medium. I ask them what the biggest challenge was. The sound of wistful huffing-and-puffing fills the room...

Sakina: It's a really complex history. You've got French colonialism, British colonialism, Spanish colonialism. You've got the arc of the French Revolution, which means that the role played by the French colonialists is constantly changing, depending on what's happening in revolutionary France. And then you've got what's going on in Haiti (then Saint Domingue), interacting with all of that. It's quite a complicated story with lots of backwards and forwards and people switching allegiance. At one point, the enslaved people, first of all they're acting purely on their own, then at one point, they align with the Spanish...

Nic: ...who owned the other half of the island.

Sakina: Then revolutionary France abolishes slavery in their empire, and they (the enslaved) align with France, then against the Spanish and also against the British, who invade. Haiti, or Saint Domingue, as it was called at the time, was a hugely profitable colony. So after all the upheaval against the French, both Spain and Britain try and take the colony for themselves. We felt our job was to try and use the illustrations to make all of that much clearer and easier to follow, which I think we've done, but it was a job unpicking all of that.

The narrative leads the reader through highly nuanced events, with an epic cast of characters (thirty two in total) and a overwhelming sense of the chaos and unpredictability of a bloody revolution. A lot of the action is of figures of authority presenting their impassioned arguments and philosophies as they make their power plays, which gradually builds up a picture of the motives of the key players.

The events in Saint Domingue (Haiti) are paralleled with the events of the French Revolution. As France changes its position on slavery from abolition, back to wanting to re-instate slavery again, so does Louverture and his army have to re-align itself. As Napoleon takes control of the revolution in France, he decides to re-capture and re-impose slavery upon the formerly enslaved peoples to set an example for the rest of the colonies. I found myself getting confused at times but the through-line keeps driving things forward and in the end it didn't matter. I found it was more helpful to re-read later rather than trying to make sense of it all first time around. Here's Nic's potted history of the period contained within the book.

(NB, The geographical names Saint Domingue and Haiti are both used, although technically Haiti did not yet exist until January 1804).

Nic: So, the previously enslaved people, led by their own leaders, one of whom was Toussaint Louverture, were aligned initially with Spain, who were the colonial masters of the other side of the island (of Hispaniola), which is now the Dominican Republic. They aligned with the Spanish in order to get guns and supplies to fight the French. Meanwhile, back in France, the political situation has changed. The Jacobins have come into power and by 1794, the French Revolution reaches its most radical stage. They abolish slavery under pressure from what's happening in Haiti. So, at that point, the previously enslaved army switch sides. They join the French who they've been previously fighting against. So now they are against the Spanish. Then the British invades, because the Spanish and the British want this island, because there's so much money to be made, and they don't believe that they can be beaten by enslaved people. So they have now beaten the Spanish, they've beaten the French and now the British invade. They fight with the British between 1794 and 1798 and the British suffer one of the largest military defeats in British history and go home with their tail between their legs. Back in France, in 1799, the counter revolution of Napoleon happens. The French Revolution is degenerated into the dictatorship of Napoleon, who is a massive racist. And also, now all the planters, who had been out of favour back in 1794, are now back in favour, and they're like, 'we want our colony back. Get us our colony'. So Napoleon sent out the largest fleet in history to re-invade the island. They turn up claiming that they're there to re-invade. Louverture wants to make peace. They've been at war for ten years at this point. They kidnap him (Louverture) and he is taken on a prison ship back to France, where he is left to die in a freezing prison cell in the Alps, which you can imagine, for a guy who comes from the Caribbean, would be a pretty terrible death.

News gets back to Haiti, or Saint Domingue at the time, that Toussaint Louverture is dead, and also that the French have restarted slavery in other islands. Because basically what happens when the French ended slavery in 1794, they ended it in the whole of the Empire. So the people in Haiti liberated slaves all over the world for a short amount of time. So they (the formerly enslaved peoples) hear that on other other islands, like Guadalupe and in Guyana, the French are re-instating slavery. So then there's this massive uprising of the people. It's no longer a war of armies and battles, set battles, stuff like that, which largely it had been for a long time. It was now a full blown revolution, a transformation of society and the French, specifically the French, were pushed into the sea. Literally, pushed into the sea. Napoleon was defeated, which led to the Louisiana Purchase, because Napoleon switched his interests from the Americas over to India and the East, once he realized he'd lost Haiti and he was not going to get it back. So they then sold Louisiana and the whole stretch of land from New Orleans all the way up to Canada. So the Americans have doubled the size of the continental United States in a stroke, which was very bad news for the indigenous people in that part of the world.

Adam: So how did they beat Napoleon? How did they push him into the sea?

Nic: The reason that the colonialists had a terrible time in Haiti is because the Haitian people knew the land and they used yellow fever as a weapon of war. So, for example, the British and the French lost a lot more soldiers to yellow fever than they did to fighting, and that's because Haitians, the Haitian revolutionaries, would hold them during the summer months, during mosquito season, in swampy areas or near the sea, and they would just die in their thousands. So part of the reason that they won is because they used their knowledge of the land. But they had a far greater knowledge of the land, of how to fight in that land, than white colonial troops.

Sakina: The idea is that this is a story of the mass of Haitian people, and it's their story. We really wanted to show that visually, because a lot of the dialogue is this debate with major figures, because he's (James) trying to tell key important things that happened. But visually, we wanted to make sure that actually, it feels like a story from below and a revolution from below and involving lots and lots of ordinary people. And we also wanted to make sure that the pictures of the enslaved people look like real people, like individuals with real lives. And we didn't draw a mass homogeneous mob. It was really important to us that every person we drew, you believe they were a real individual person. So, partly because of that we created a series of what we call non-speaking characters who you can follow from the beginning to the end of the book, sometimes in the foreground pictures, sometimes in the backgrounds, but you can follow them visually. And some of those we added into the character list. So actually, we added to the number of characters visually. And to some extent, you can ignore those non-speaking characters. You don't have to follow any of that. I think most people won't notice, but it kind of adds to the richness.

It took Nic and Sakina well over a decade to complete Toussaint Louverture from its initial inception to publication. That this book even exists at all is a minor miracle and testament to Nic and Sakina's dedication to pursuing a great idea right to the very end. Original works like Toussaint Louverture define what is possible within the graphic novel medium and this epic history is as ground-breaking as anything I've seen in recent times.

Comments